Nujeong: Towers and Pavilions

by Shin Sang-Phil December 10, 2021

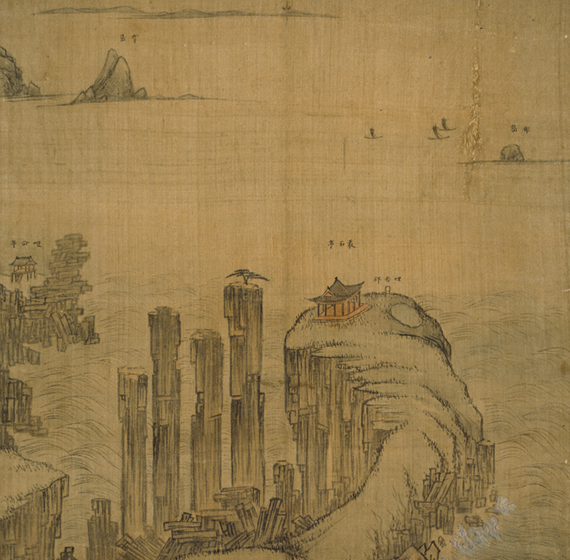

Painting of Segeomjeong Pavilion

Yu Suk (1827–1873)

© National Museum of Korea

The Construction of Nujeong and the Scholar-officials in the Joseon Dynasty

People of Korea today would probably find the word nujeong unfamiliar; but they would understand the words nugak (tower) and jeongja (pavilion) without difficulty. Nujeong is a word composed of the first letters of those two words. During the five hundred years of the Joseon Dynasty, towers and pavilions were built nationwide wherever there were beautiful mountains and clean water; many remain local attractions to this day. Even today, neighborhood parks are equipped with little pavilions, commonly called palgakjeong (octagonal pavilion) or noinjeong (pavilion for the elderly) where people can sit and rest while out on a walk. Towers are larger in scale than pavilions, elevated so that the floor, laid out with wood, stands one or more stories high above the ground. Walls and doors are installed on occasion to create room-like space, but mostly, towers consist of pillars and a roof, so that people can look out over the landscape from the inside. Octagonal pavilions have roofs that are octagonal in shape, generally with a square or rectangular plane and in some special cases with a hexagonal or octagonal, and sometimes even a cross or fan-shaped plane.

Although the Joseon Dynasty is spoken of in particular here as the era in which towers and pavilions were built, such structures existed even in the days of the three Han states, dating back two thousand years. Their number, however, wasn’t sufficient to form a culture until the Goryeo Dynasty; hence, the focus on the Joseon Dynasty, when the construction and use of towers and pavilions saw an explosive increase. While Buddhism constituted the main axis of culture until the Goryeo Dynasty, Confucian ideas formed the basis of the principles for running a society during the Joseon Dynasty, with sadaebu as the main axis of power. The word sadaebu refers to scholars—sa—who had yet to take up a position as a government official, or who had resigned from government post, and officials—daebu—who were in charge of government administration. These scholar

-officials were intellectuals who had mastered Chinese classics, men of letters, as well as government officials. Brought together by the philosophy of Confucianism and connected through academic and regional ties, they developed a society and culture of their own. Towers and pavilions were the places of their gathering. They served as venues for literary gatherings, where the men recited poetry; as places for conducting administration as well as holding banquets; and as command posts with a view from on high during war emergencies. But above all, they were places of gathering and entertainment, for an overall enjoyment of literature and the arts.

Regional geography books, including the sixteenth century cultural geography book, Augmented Survey of the Geography of Korea (1530), mention towers and pavilions along with public offices while discussing the natural characteristics of a region, as well as the people, family names, and regional products. The number of towers and pavilions noted in these books comes to about eight hundred. Studies on towers and pavilions indicate that the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries saw the greatest increase in their number, with nationwide construction but mostly in the Gyeongsang and Jeolla provinces. The fact that the regional base of the scholar-officials was in these two provinces can be seen in the number of towers and pavilions constructed there. It is understood that the foundation of a society centered around scholar-officials was laid out through the fifteenth century after the establishment of the Joseon Dynasty in 1392, based on which the culture of scholar-officials, centering around towers and pavilions, flourished in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Just as European salon culture blossomed during the eighteenth century, the tower-and-pavilion culture came into bloom in fifteenth century Joseon.

The Site of Nujeong Culture That Sang of the Wind and the Moon

I devoted ten years to building my humble abode of three rooms

One for me, one for the moon, and one for the cool wind

No room for the river and the mountain—I shall enjoy them as they are

The above is the second stanza of the three-stanza poem, “The Song of Myeon-ang-jeong,” about the Myeon-ang-jeong Pavilion in Damyang, South Jeolla Province. The pavilion was built by Song Sun (1493–1582), a military official of the early Joseon period, who returned home after leaving his government post the year he turned forty-one. The poem is a major work representing the Korean nujeong culture, revealing its essence.

In the first line of the poem, the author states that the pavilion took ten years to complete—he must have put a lot of thought and effort into the process, including finding a site for the building and purchasing the wood. He calls the pavilion his “humble abode,” the original Korean word choryeo meaning a hut made of straw and weeds. The word gan in the original phrase, choryeo sam-gan (three-roomed hut) is a unit that measures the size of a building. It refers to the space between two pillars, about two meters wide. The phrase sam-gan indicates that the frontal view of the pavilion shows four pillars, and a width of about six meters. The owner of the pavilion, however, states that he will take just one of the small pavilion’s rooms for himself, and set the other two aside for the moon and the wind, his tenants-to-be. This is witty poeticization of the nature-friendly aspect of the pavilion, whose simple pillared structure allows in the cool, fresh wind and the bright moon. Song Sun finishes the stanza with the playful words that he will enjoy the river that flows in front of the pavilion and the mountains surrounding it as they naturally are, for there is no room for them in the pavilion.

Through such simple yet affectionate personification, the author describes the Myeon-ang-jeong Pavilion as a part of the natural landscape; then he slips himself into the poem as well, as the owner who enjoys the harmony of it all. In that respect, he has demonstrated the meaning of the phrase, “borrowed scenery,” used in explaining the aesthetics of Korean architecture. The phrase is used to describe how Korean architecture exists as a part of the surrounding landscape. Unlike Chinese and Japanese gardens, in which the landscape is artificially recreated by men, Korean architecture is designed so that a river flows in front of it and a mountain stands behind like a folding screen, so as to make the surrounding nature seem a part of the garden itself. Such building planning is commonly called bae-san-im-su (mountain in the back and a river in the front). Song Sun’s Myeon-ang-jeong Pavilion, too, is located in a spot where the surrounding mountains and river feel like a part of the garden, with the moonlight and the wind finding their way into the pavilion. It seems that there is no work that better captures the characteristics and culture of Korean towers and pavilions. Song Sun also penned the following poem using Chinese characters.

Many a scenic spot lies in the southern province—

Everywhere I go stands a pavilion with beautiful scenery.

I live a life of leisure in the village of Gichon,

And you reside in Seongsan.

Our families have been friends for generations

And we come and go like a family.

I may stop by on a horse any day

So do not bolt up the pine wood door.

Sigyeongjeong and Hwanbyeokdang

The two pavilions are like brothers now.

The streams and mountains are bright as silk

And houses, tile-roofed and thatch-roofed, are scattered like stars.

Together we enjoy the beauties of nature

As they do in the gardens of all the houses.

But one thing saddens me—I miss the old man at Soswaewon

For he lies in a grave covered with withered grass.

This poem was written by Song Sun for Sigyeongjeong, a pavilion that belonged to Seohadang Kim Seong-won (1525–1597). The southern province spoken of in the poem refers to Jeolla Province. Song depicts the nujeong culture of sixteenth century Korea, saying that there are pavilions in all the beautiful landscapes of Jeolla Province. Sigyeongjeong, Hwanbyeokdang, and Soswaewon, which appear in the poem, are located at the foot of Mudeung Mountain to the east of Gwangju, Jeolla Province; Myeon-ang-jeong stands about twelve kilometers away to the north.

Sigyeongjeong was built by Kim Seong-won in 1560 for Seokcheon Im Eok-ryeong (1496–1568), his father-in-law. It is told in The Chronicle of Sigyeongjeong that Kim Seong-won asked Im Eok-ryeong to come up with a name for the pavilion, which he did based on a story in the Book of Zhuangzi that tells of a man who was afraid of his own shadow and wanted to run from it, and whose wish came true when he entered the shade of a tree, upon which his shadow disappeared. The word sigyeongjeong means a pavilion where even a shadow stops for a rest.

Hwanbyeokdang is a pavilion built by Kim Yunje (1501–1572). As the story goes, Kim, while taking a nap at the pavilion, had a dream about a dragon ascending to heaven from the stream in front of the pavilion; upon waking he went down to the stream and found a tall and handsome boy standing there, for whom he arranged a marriage with his granddaughter. The boy was Songgang Jeong Cheol (1536–1593), who served as the first vice-premier.

Lastly, Soswaewon was a garden created by Yang Sanbo (1503–1557), who decided to live a secluded life when his teacher Jo Gwangjo (1482–1519) was poisoned to death in the literary purge called Gimyo sahwa. The garden, as well as the pavilions within, such as Jewoldang and Gwangpung-gak, demonstrates an aspect of the Korean garden and pavilion culture.

Just as Song Sun wrote poems about his pavilion and displayed his literary talent through the neighboring Sigyeongjeong, the scholar-officials of the Joseon Dynasty left behind records on the history of pavilions. Haseo Kim Inhu (1510–1560) wrote The Thirty Views of Myeon-ang-jeong and The Forty-eight Views of Soswaewon, and Jeong Cheol wrote The Eighteen Views of Sigyeongjeong, conveying their affection for the pavilions belonging to prominent figures of Jeolla Province. Jeong Cheol also wrote The Song of Seongsan, which sings of the beauties of the four seasons of Seohadang and Sigyeongjeong, comparing them to paradise and lands of enchantment; the nujeong culture, which flourished through literary men among the scholar-officials, is once again confirmed in the poem.

Bubyeokru Pavilion, Banquet Hosted by the Governor of Pyeongan Province

Gim Hongdo (1745–1806)

© National Museum of Korea

Stories Related to the Four Major Pavilions of Korea

Pavilions, each consisting simply of a wooden floor and a roof, were built near mountains and rivers for people to stop and take a little rest; but with time, they evolved into forums for meetings and poetry readings held by the literary intellectuals of the Joseon Dynasty. Some of the poems written in Chinese characters, three-stanza poems, lyrics, and records composed in these pavilions were framed and hung there and remain as works of art. The more number of works by prominent figures hung in a pavilion, the more renowned the pavilion became. Such are the three major pavilions of Korea: Bubyeokru of Pyeongyang, Chokseokru of Jinju, and Yeongnamru of Milyang. The two pavilions of South Gyeongsang Province are of considerable size, with a frontal width of five gan, and side width of four. A thousand poems and prose have been written on each, which speaks of their fame. In recent years, Gwanghallu of Namwon is counted (instead of Bubyeokru, which sadly can’t be visited because of its location in North Korea) as one of the three major pavilions.

These pavilions, however, are famous not only for their long history, great scale, beautiful paintwork, and the poetry and prose written about them. Each pavilion comes with a beautiful story about women of integrity that adds color to them. During the Japanese Invasion of Korea, Gye Wol Hyang of Bubyeokru aided in the beheading of the enemy commander; Nongae of Chokseokru cast herself into the river with the enemy commander in her arms, as a result of which both died. The two, called “honorable gisaeng,” added to the reputation of Bubyeokru and Chokseokru. Likewise, Arang of Yeongnamru faced death in order to maintain her chastity; and Chunhyang of Gwanghallu, despite her status as a gisaeng, consummated her love with Yi Mongryong, the son of the district magistrate. This Chunhyang is the heroine of The Tale of Chunhyang, the eternal Korean classic and the quintessence of pansori, or Korean opera. It was at Gwanghallu that Chunhyang and Yi Mongryong had their first encounter, as depicted in the following passage.

Young Master Yi rushes to Gwanghallu on his donkey, and upon arrival he beholds a splendid house of beautiful paintwork with intricately patterned doors. He gracefully dismounts the donkey, steps onto the staircase, and looks all around . . . Chunhyang, the daughter of Wolmae, a gisaeng living in the town . . .,

gets on a swing and looks at the mountains and streams in the distance flaunting their spring colors; her sudden ascent and descent are like those of a young swallow flying in the spring sky, or of the Vega star crossing the Ojak Bridge on the seventh day of the seventh month . . .; Young Master Yi, sitting high on Gwanghallu, looks at the mountains and streams to his left and right . . ., then at the greenery in the mountain in front of the pavilion; ecstatic in body and mind, he stares at the movements of the red and yellow sun through the leaves, his shoulders moving up and down and his hand above his eyes.

This is the scene in which Yi Mongryong, who has come to Namwon, the place of his father’s new post—and who has abandoned his studies to enjoy the spectacular view at Gwanghallu with his servant—becomes besotted with the beauty of Chunhyang on a swing. After Yi returns to Hanyang with his father who has served his full term in office, the new magistrate demands that Chunhyang become his mistress; realizing her love for Yi, Chunhyang resists the magistrate in order to defend her love. This is a beautiful love story of two people who met at Gwanghallu and safeguarded their love for each other despite trials.

Im Kwon-taek, a major Korean film director, adapted the tale into the movie Chunhyang (2000). An interesting point of fact is that the movie is a musical of sorts based on The Song of Chunhyang, a work performed by the master pansori singer, Cho Sang Hyun; in the movie, the acting corresponds to the songs. The movie allows the audience to enjoy on screen the love story of Yi Mongryong and Chunhyang along with the pansori, The Song of Chunhyang, as well as the beautiful scenery of Gwanghallu and a vivid look into the everyday life of the people of old Korea.

Chongseokjeong Pavillion, Album of Mount Geumgang in the Autumn of the Year of Sinmyo

Jeong Seon (1676–1759)

© National Museum of Korea

The Joseon Dynasty and the Pavilions of Hanyang

Pavilions were cultural and entertainment venues for scholar-officials, as well as a backdrop for everyday gatherings of ordinary people. Perhaps the love of the people for pavilions lay in their location, where rivers and mountains meet. Hangyang, the name of Joseon’s capital, means “a land north of the Han River,” the river that served as the lifeline of the people. Naturally, pavilions were established in scenic spots. A classic example is Apgujeong, a pavilion located in present-day Apgujeong-dong in Seoul, which belonged to Han Myeonghoe (1415–1487) who had control of the regime in the early Joseon Dynasty; another is Dokseodang, a pavilion on a hill north of the present-day Hannam Bridge, which allowed young civil officials to take a leave to concentrate on their studies; yet another, Huiujeong, which belonged to Prince Hyoryeong (1396–1486), the second son of King Taejong, on a hill north of the Yanghwa Bridge. Huiujeong means “pavilion of joyful rain,” and the following story is told in The Chronicle of Huiujeong, written by Chunjeong Byeon Gyeryang (1369–1430) at the request of Prince Hyoryeong:

His Highness came out early to oversee the farm work, and stopped by at this pavilion and bestowed upon me liquor, food, and a saddled horse. Grain seeds were being sown at the time, but there wasn’t sufficient rain. As we became intoxicated with liquor, it began to rain all day, and His Highness named the pavilion “the pavilion of joyful rain.” Deeply moved, I had the Vice Chancellor of Royal College write the word “Huiujeong” in large letters and hang it on the wall, to honor the deed of His Highness; it is my wish that you set this down to record.

The king who bestowed the name upon the pavilion was King Sejong, hailed as a good and wise king. This anecdote conveys the genuine joy of the king, who must have wished for rain as the ruler of Joseon, an agricultural society. The feelings of a benevolent ruler who truly cared for his people are fully conveyed. As told in the anecdote, kings came to the pavilion to inspect the administration of agricultural work, or the training of the naval forces that took place in the Han River. Byeon Gyeryang, who was asked to keep a record of the history of Huiujeong Pavilion, wrote the following poem near the end of his life, through which the warm sentiments generated by Korean pavilions can be appreciated.

The new pavilion that stands there aloft

Looks as though it will fly away like a phoenix.

Who has raised it up?

The benevolent Prince Hyoryeong.

The king went out to the western outskirts,

Neither for pleasure nor hunting.

Concerned he was about drought in the fields,

As the people sowed seeds of grain.

The king was sitting in the pavilion

When suddenly the rain came pouring down.

The king and the prince held a banquet

With drums beating loud and clear.

On the pavilion the king bestowed a name,

An honor unprecedented.

Prince Hyoryeong bowed his head,

Accepting the kindness of the revered king;

The prince again bowed his head,

Praying for the king’s longevity.

The prince wished that a record be kept

For the perpetuation of the tale;

I bowed and did as commanded,

Ahead of many scholars.

I looked to the distance at Hwaak Mountain

And pictured these words on its stone wall.

This tribute, carved in stone,

Will keep the tale alive for myriad years.

Translated by Jung Yewon

Shin Sang-Phil

Pusan National University

Did you enjoy this article? Please rate your experience