Gungnyeo: The Palace Women

by Jung Byung-Sul Translated by Amber Hyun Jung Kim March 10, 2022

Gungnyeo, literally “palace women,” is a term referring to all women residing in the palace who were not members of the royal family. The palace also saw the comings and goings of uinyeo (female physicians) who worked in the medical wing (naeuiwon) and female seamstresses who worked in the royal tailor shop (sanguiwon), but these women themselves were not called gungnyeo. Instead, they were known as medicinal kisaeng or tailor kisaeng who commanded the highest status of all kisaeng (trained courtesans). Since they did not reside within the palace walls, they technically did not meet the criteria of gungnyeo. Strictly speaking, gungnyeo had to be officially decreed by the court to wait upon the royal family. In his book Ojuyeonmunjang-jeonsango (A collection of writings on various topics by Oju), Lee Gyu-gyeong further distinguishes between gungnyeo and gungbi (court slaves) by stating, “Typically, gungno (court servant) held the low-level court post of byeolgam while the gungnyeo fulfilled the role of ladies-in-waiting known as hang-a as befitted their status. Gungbi were known as susari, or in the common tongue, musuri (female slave).” And yet, it was not unheard of for female slaves residing in the palace to be alternatively known as gungnyeo, so it appears the two terms gungnyeo and gungbi were used interchangeably to a certain extent.

As such, gungnyeo took on many tasks around the palace, such as the jimil nain who waited closely on the king and queen, as well as other nain who variously worked in the chimbang (sewing room), subang (embroidery room), naesojubang (kitchen for daily meals), oesojubang (kitchen for banquets and feasts), saenggwabang (desserts kitchen), sedapbang (laundry room), sesugan (laundry room for the king and queen), and deungchokbang (room for lanterns and candles). Crown Princess Hyebin is said to have overseen approximately thirty to forty sanggung (court ladies) and sinyeo (ladies-in-waiting), and since this was the number of gungnyeo who waited on a single crown princess, we can assume that the number of gungnyeo who waited on the king and queen was significantly higher.

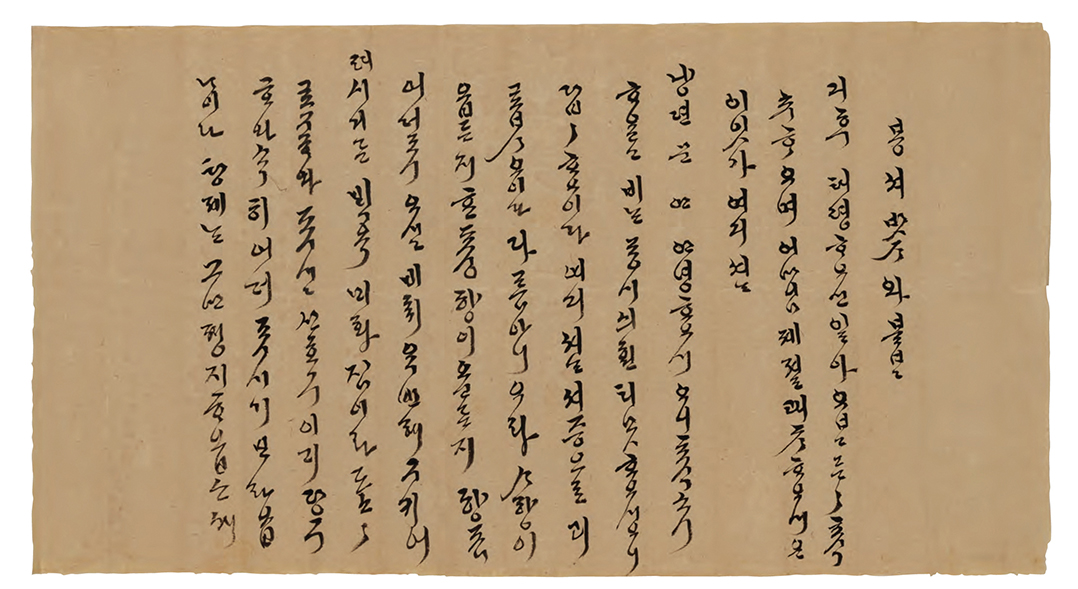

A letter written by a sanggung in cursive hangul

© National Palace Museum of Korea

Recruitment and Promotion of Gungnyeo

Gungnyeo were not hired on some set, regular basis; rather, they were recruited whenever there was an opening or when the court was being newly outfitted under new leadership. The postings weren’t typically advertised widely; instead, the court received recommendations and carefully picked from a vetted shortlist of candidates, often through word-of-mouth. In some cases, the queen or crown princess was allowed to bring their former female servants from their family home with them to the palace.

In Hanjungnok (The Memoirs of Lady Hyegyeong), there are several passages that allude to the gungnyeo selection process. After the birth of Crown Prince Sado, a new royal hall was quickly put together for the young boy prince. In the process, King Yeongjo brought in the gungnyeo who formerly served under Queen Seonhui, the queen to former king Gyeongjong, to wait on the crown prince. This informs us that the gungnyeo were typically made to leave the palace if the royal person they served was no longer present or alive, and also that in at least one instance, the king himself selected the gungnyeo. Another interesting case involved the recruitment of nain to serve the Crown Prince and Crown Princess. For this role, the court looked to hire from among the daughters of court officers who held the position of byeolgam and those who held the higher promoted position of sayak. The book tells of how one Kim Su-wan, who held the post of sayak, reportedly attempted to prevent his daughter from becoming a gungnyeo by seeking to influence King Yeong-jo’s consort. This man had apparently worked to pressure the king’s own concubine to stop the court from selecting his daughter to work as a nain. In Hyebingungilgi (Palace journal of the Crown Princess Hyebin), there are records of one Kim Do-heung, a byeolgam of the court, who faked the death of his daughter Han-mae, a privately owned servant, to prevent her from going to work in the palace. For this misdeed, Kim was later punished. In another instance, Kim Seong-gyeong, who served as a seowon at Yongdonggung Palace, was purportedly punished for failing to prepare his daughter sufficiently for her role as a nain. These examples shed light on the common practice of hiring gungnyeo from among the daughters of low-ranking court officials, and show that at least several of them resisted and fought to prevent their daughters from working such positions.

The Life of a Gungnyeo

The life of the gungnyeo is well illustrated in the hangul descriptions found in Gungnyeosa (The song of the gungnyeo) that is assumed to have been written by a gungnyeo, date unknown. In the book, the typical attire of a gungnyeo is described as such: “Before each morning assembly and evening greetings at Jangchungak Hall within Mianggung Palace (residence of the King of Han Dynasty China), we are required to don long skirts that flow down from our waist, a well-adorned big wig for the head, along with a headpiece and ribbon that are pleasing to the eye.” The unknown author of the book goes on to describe the joys of palace life by remarking how “the always upright Sanggung Kim and the pure-at-heart Sanggung Lee called each other ‘sister’ and swore to be friends forever. In their excitement, they called me to join them as they banged on jade bottles as if they were drums and shared drinks aplenty as we danced and sang and had an altogether merry time.” However, the author also wrote of the sorrows of homesickness: “My parents and siblings live no more than 10 ri outside the walls of Hanyang, and yet I long for them during the day and dream of them at night enough to make my insides melt and quiver even if they were made of steel and stone. When, after much effort, I finally obtained a pass to visit my family outside the palace, I rushed outside, greeted my parents, siblings, and relatives, and stayed with them for a day, which was not entirely enough for us to catch up. Then, when our time was up and I had to return to the palace, I leapt up, clutching my pass in my hands, and raced back to the palace in a hurry while promising my family to see them next spring.”

Married women could not work in the palace, which meant that gungnyeo were typically brought in as pre-teen girls who would be trapped inside the palace for the rest of their lives, but other than the grief of not being able to see their families and loved ones, they were allowed to share in the riches and luxuries of the palace. The women were also adept at entertaining themselves, so their lives must not have been all bad. At times, the gungnyeo threw their own parties; in Jeongjosillok (Annals of King Jeongjo), the king himself saw fit to ban the feasts of gungnyeo that were conducted outside the palace walls. “The gungnyeo were seen cavorting with kisaeng and playing loud music as they entertained each other on boats while being waited on by aengnye (common slaves) and other gungno (palace slaves), to the point that huge crowds gathered by the riverbanks. On extreme instances, the gungnyeo were seen entering the riverside pavilions and vacation homes of merchants; other obscene, lascivious conduct will not be repeated here, as to not give rise to more ugly talk.”

This description shows that gungnyeo were known to entertain themselves in the company of kisaeng with music and rowboats, and enjoyed free access to the gazebos and summer homes of rich merchants. From this, it’s clear not only that the gungnyeo knew how to have fun, but also that they commanded a high level of authority. Some scholars have concluded that gungnyeo were not allowed breaks, but the accounts in Gungnyeosa show that the women were granted at least one sojourn a year outside the palace walls. We can assume that depending on the year or the king, gungnyeo were allowed time off in some, but not all, cases. What’s true was that the gungnyeo remained confined to the palace until their deaths, never being allowed to marry or be reunited with their loved ones, but that they somehow managed to carve out relatively prosperous and stable lives of their own within their community.

A gungnyeo from the late Joseon period

© National Folk Museum of Korea

Perception and Status of the Gungnyeo

Hanjungnok offers telling glimpses into the authority and influence enjoyed by gungnyeo in general, but in particular by the sanggung (higher-ranking gungnyeo). Lady Hyegyeong is said to have reminisced that Choi, her attending lady-in-waiting, who received her on the day she came to live in the palace, was “not one to be taken lightly, as she had a firm and thorough grasp of the history of the royal family and court etiquette.” Later, Lady Hyegyeong again remarked on the strict customs of Sanggung Choi. Once, when Crown Prince Sado was being unfairly scolded by his father King Yeongjo who wrongly believed that his son had drunk liquor, Sanggung Choi stepped up to defend the poor prince when no one else dared. None of the court’s ministers (jeongseung, panseo) dared speak up on behalf of the prince, yet a lady-in-waiting mustered the courage to do so. Sanggung Lee, who began her career as a nain and later became one of Yeongjo’s concubines, is said to have scolded the queen herself, Queen Jeongsun. When the queen’s family wrote the queen a letter criticizing Crown Prince Sado, she shared this letter with King Yeongjo. When she did so, the sanggung is said to have chastised the queen directly, saying that no queen had the right to criticize a crown prince. This incidence is a clear testament to the compelling authority of the court’s sanggung, who were proud bearers of the court’s customs.

In the rapidly evolving whirlwind of political power struggles in the palace, the gungnyeo often found themselves swept up in the intrigue surrounding them, while at other times, merely observed what unfolded. In either instance, however, the gungnyeo always remained an important agent within the palace walls. It appears that they did not always have a positive view of the court’s power and authority. Kim Myeong-gil, known as the last sanggung of the Joseon Dynasty, concluded in her memoir, “Spending the entirety of my life—all sixty years—inside the palace walls, I have come to believe that most of the folks who call themselves royalty or nobility are in fact empty shells. Many of them spent their lives in humiliating comfort, degrading themselves even more than the lowliest commoners or kisaeng; such stories are too unfortunate to simply ignore.” One can’t fault Kim for waxing pessimistic as she had directly witnessed the fall of the Joseon court, but the fact remains that gungnyeo were key observers of those closest to power.

Translated by Amber Hyun Jung Kim

Jung Byung-Sul

Professor of Korean Literature

Seoul National University

Did you enjoy this article? Please rate your experience